Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): A PRACTICAL APPROACH

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is common, accounting for more than 5.6 million physician visits each year. From 10% to 20% of adults in Western countries and nearly 5% of those in Asia experience GERD symptoms at least weekly. The prevalence of GERD symptoms is increasing by about 4% per year, in parallel with increases in obesity rates and reduction in prevalence of Helicobacter pylori over the past several decades. However, patients may not have symptoms of GERD even if they have objective evidence of it such as erosive esophagitis or Barrett esophagus.

It is a chronic condition caused by changes in the gastroesophageal valve (GEV) that allow contents to flow from the stomach back into the esophagus. Left untreated, GERD can be a lifelong disease. It can lead to bothersome symptoms, which can vary from mild or moderate to severe depending on the person.

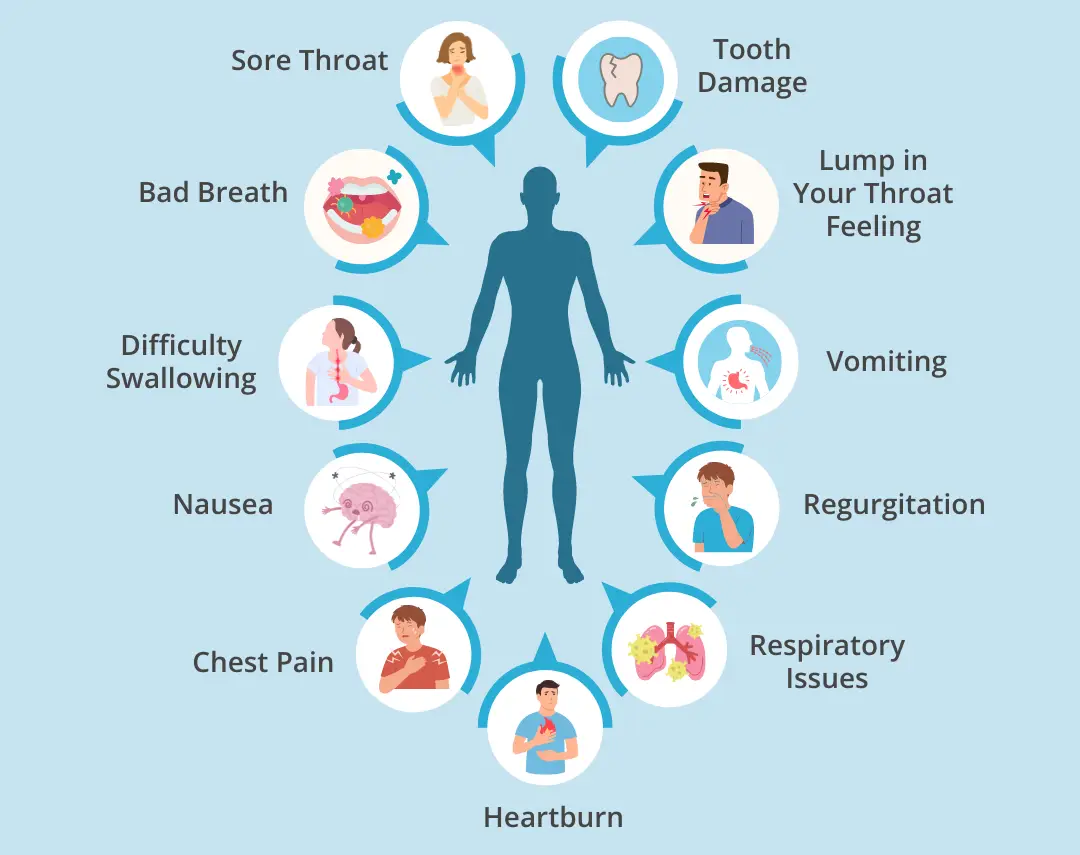

- ⦁ Typical symptoms: burning sensation in the chest (heartburn), regurgitation of food or sour liquid (acid reflux) and difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

- ⦁ Atypical symptoms: sensation of a lump in the throat (globus), asthma, chronic dry cough, chronic sore throat, laryngitis and hoarseness, dental erosions and non-cardiac chest pain

GERD is not an “acid” problem. Instead it is caused by an anatomical issue. The acid our stomach produces is important for digestion, killing harmful bacteria and helping with the absorption of electrolytes and other nutrients from the foods we consume GERD occurs when the valve between the stomach and the esophagus is not working properly and fails to keep contents in the stomach. Medications may offer mild to intermittent symptom control, but they do not stop or prevent reflux. Additionally, those who are or may become dependent on daily medication may develop severe complications from GERD, even if no symptoms are experienced. When left untreated, GERD can lead to other health complications including:

- ⦁ Damage to the throat or esophagus

- ⦁ Inflammation or narrowing of the esophagus

- ⦁ Respiratory complications

- ⦁ Barrett’s Esophagus

- ⦁ Esophageal cancer

Love spicy food? Eating out late? Eating large meals rather than snacking? What about eating on the couch in front of the TV? (I mean who doesn’t?) All of these daily eating habits could set you up for a rough night of reflux symptoms and other common symptoms of GERD at night. There are also other reasons as to why GERD might flare-up during sleep that are less about healthy habits and more about how the body is functioning. For example, people with sleep apnea might be more likely to experience GERD.

One explanation is: “When you lie down to sleep—or even if you recline on the couch right after dinner—gravity is no longer on your side and the acid from your stomach can more easily escape up into the esophagus.”Here are some questions to ask yourself to identify reasons why your chronic acid reflux is worse at night:

- ⦁ Do I walk or move after big meals? Or am I stationary, lying down, or hitting the couch?

- ⦁ Am I eating to satiety or past the point of satiety frequently?

- ⦁ Am I eating mindfully? Slowly and sitting upright?

- ⦁ Am I eating more at night than during the day?

- ⦁ Am I eating spicy or greasy food more often than vegetables or fruits? Do I drink caffeinated beverages or alcohol frequently?

- ⦁ Am I eating right before bedtime? And can I potentially eat dinner earlier?

Eating and Lifestyle

- ⦁ An increase in GERD symptoms occurs in individuals who gain weight.

- ⦁ A high body mass index (BMI) is associated with an increased risk of GERD.

- ⦁ High dietary fat intake is linked to a higher risk of GERD and erosive esophagitis (EE).

- ⦁ Carbonated drinks are a risk factor for heartburn during sleep in patients with GERD.

Approaches to reflux should focus on best clinical practice, with treatment of the symptoms being the priority.

- ⦁ It is wise to choose the lowest effective dose of prescription drugs.

- ⦁ For patients with mild symptoms, and some patients with NERD, self-directed, intermittent PPI therapy (“on-demand therapy”) is a useful management strategy in many cases.

- ⦁ At the primary care level, PPIs or a combination of alginate-antacid and acid-suppressive therapy can be prescribed at the physician’s discretion for combination therapy, which may be more beneficial than acidsuppressive therapy alone.

- ⦁ For better symptom control, patients should be informed about how to use PPI treatment properly; optimal therapy may be defined as taking the PPI 30 to 60 minutes before breakfast, and in the case of twice-daily dosing, 30 to 60 minutes before the last meal of the day as well. Patients in whom full-dose PPI treatment fails, with or without adjuvant therapies, may benefit from a trial ofstep-up therapy to a twice-daily PPI.

- ⦁ Twice-daily PPI therapy may not work for a proportion of patients, either because the symptoms are not due to acidreflux—when an alternative diagnosis should be considered— or because the degree of acid suppression achieved is insufficient to control the symptoms. Referral to secondary care should be considered for “PPI-refractory” patients.

- ⦁ OTC antacids show disappointing results in patients

A schematic representation of management of GERD is shown below:

KEY POINTSThe diagnosis of GERD is mainly symptom-based and often does not require endoscopic confirmation. Endoscopy is warranted in patients with red-fl ag symptoms such as dysphagia, anemia, weight loss, bleeding, and recurrent vomiting. PPIs are the first-line medical therapy. Histamine 2 receptor antagonists are mainly used to treat breakthrough nocturnal symptoms. Endoscopic and surgical options exist but are pursued only if medical therapy fails.